Amid COVID-19, Portugal’s ethnic minorities really feel closely policed | Portugal Information

For Sandra Pina, opening a kiosk snack bar in Lisbon was a dream come true.

“When I came to Portugal, I was selling groceries on the street, coming in rain or shine before finally becoming a market seller. But having my own business is more than I could ever have imagined,” she told Al Jazeera .

The Doces da Sandra (Sandra’s sweets) is brightly painted, spotlessly clean, and sells homemade cakes and deep-fried Cape Verdean pastries, as well as beer and coffee. It serves customers in Casal da Boba, a neighborhood in a suburb of Lisbon.

Pina opened his business in August this year when the COVID-19 infection rate was low in Portugal and food and beverage outlets were reopening across the country – especially those with outdoor areas and take-away services like the kiosks.

“Lots of people came by and everything went really well,” she says proudly, “until the police came over.”

In September the police ordered Pina to close the kiosk for two weeks and leave her with no income.

“They didn’t even give me time to clean up, so any groceries I had stored went away when I could open them again. Business hasn’t been the same since then – people don’t want to come because they see the police here all the time. “

Sandra Pina in her kiosk [Ana Naomi de Sousa/Al Jazeera]According to Pina, the PSP police said they were sent by the DGS (Portugal’s National Health Agency, responsible for deciding on COVID-19 public health measures) for selling beer that is currently in Portugal after 8 p.m. Food is allowed to accompany you.

Another reason often given for mandatory closings is that cafes allow people to gather in large groups. But here, as in many districts in the suburbs of Lisbon, the residents do not feel treated the same as the people in the rest of the city.

“If you go down the street in the white quarters, you will see that the cafes are full of people who drink, sit in groups and, for example, play cards,” says José Sinho Baessa da Pina, an organizer of the municipality of Casal da Boba.

“They treat us very differently up here. It’s like they’re not here to protect us – they’re here to provoke us. “

This feeling is reflected in the outskirts of Lisbon, in low-income areas and especially in areas with significant Afro-descended and Roma communities, where there have been numerous closings and where relations with the police are strained.

“We had complaints almost every day from companies in the suburbs who said, ‘We were closed, but the white cafe owner on the opposite corner was allowed to stay open,” says Mamdou Ba, one of the directors of the anti-racism organization SOS Racismo advocates police violence in Portugal.

“Racized neighborhoods here were always monitored differently,” says Ba. “But COVID not only made this state of emergency the norm, it also brought legal and institutional support for it.”

Images of a public health operation in May this year in the Bairro da Jamaica neighborhood, where residents waited for years to be relocated by a precarious set of self-made towers, caused further anger.

More than 50 armed police officers in protective clothing escorted a group of public health officials in quarantine suits to shut down eight local cafes during a COVID outbreak (the number of cases is contested by local residents and since then the number reported in the press fell from 49 on 19).

Several television crews had been invited to film the operation and coverage, centered on rumors of a local party as the source of the outbreak, generated strong reactions on national news.

Closed commercial units in the Casal da Boba district [Ana Naomi de Sousa/Al Jazeera]Ana Rita Alves, an anthropologist working on housing and racism in Portugal, says: “The media has contributed to the criminalization of racialized people in the periphery, conveying the idea that these are spaces that need to be cleaned and“ civilized ”. as if they were a problem that needs to be fixed ”.

Closed commercial units in the Casal da Boba district [Ana Naomi de Sousa/Al Jazeera]Ana Rita Alves, an anthropologist working on housing and racism in Portugal, says: “The media has contributed to the criminalization of racialized people in the periphery, conveying the idea that these are spaces that need to be cleaned and“ civilized ”. as if they were a problem that needs to be fixed ”.

To the suggestions that the police in the suburbs are heavier, Alves replied: “In my own neighborhood in the center of Lisbon, I don’t see the police running around in emergency vehicles or wearing protective clothing when they drive around at night to see if people are on their way – but that’s exactly what they do in the periphery. “

Ba is also concerned about the normalization of police work: “The most vulnerable people in our society are being turned into a threat. And the public’s reaction is simple – well, that’s fine because this is a state of emergency, isn’t it? ”

PSP police said in a statement to Al Jazeera: “PSP operations are carried out in all major cities without prioritizing the periphery in relation to the center and without targeting any particular type of facility.

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, the PSP has been consistently performing its functions across the country, as evidenced by the myriad of operations that are being followed by the media.”

But the residents of Cova da Moura say the police show up regularly, either in protective clothing or in emergency vehicles through the neighborhood.

“They’re using COVID as the perfect excuse,” says Flávio Almada, a community organizer and one of the petitioners in Portugal’s best-known police brutality case.

“The people here have usually taken it very seriously, they are sensible and they protect each other,” says Almada. “In reality, however, they cannot stop going to work or using public transport. The people here work to survive. “

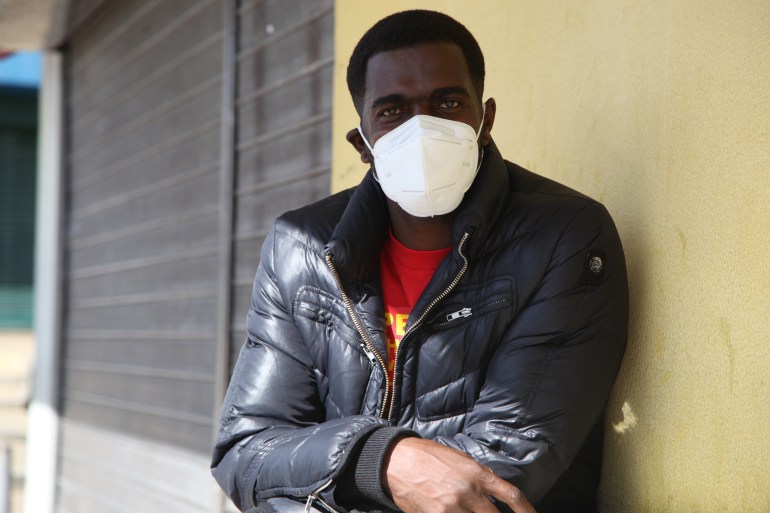

José Sinho Baessa de Pina, a community organizer, says the police treat us very differently up here. It’s like they’re not here to protect us – they’re here to provoke us. ‘ [Ana Naomi de Sousa/Al Jazeera]De Pina paints a similar picture in Casal da Boba.

José Sinho Baessa de Pina, a community organizer, says the police treat us very differently up here. It’s like they’re not here to protect us – they’re here to provoke us. ‘ [Ana Naomi de Sousa/Al Jazeera]De Pina paints a similar picture in Casal da Boba.

“Although the impression in the media is that the periphery is the epicenter of COVID, we actually hardly had any cases here – but we are the most exposed.”

He takes the bus early in the morning to go to the public hospital, where he works as a security guard.

“The lower class, the black class, has not stopped working all the way through the pandemic. Every day the buses from here are full and the trains to Lisbon are full of cleaners, construction workers, supermarket workers and security guards like me. We are on the front line. “

Combating the pandemic is much more difficult in areas with precarious housing and overcrowding.

Overall, Portugal did relatively well in the first wave, with a quick, strict lockdown and early introduction of a testing system, followed by a relatively low mortality rate.

However, the lockdown is expected to have dramatic consequences for a historically weak economy that has become increasingly dependent on tourism in recent years, accounting for 15 percent of the economy and 17 percent of employment.

GDP is expected to decline by 8 percent this year – and unemployment is set to rise.

With cases soaring, the outlook is bleak for those in low-income neighborhoods where job insecurity is compounded by factors such as immigration status.

“The people here live from hand to mouth,” says Almada, who like de Pina was heavily involved in the distribution of food and other important goods on site during the pandemic.

“With all of the recent hospitality shutdowns, we’ve heard from many people in the community who have suddenly been laid off … the effects could be dire.”

Back at her kiosk, Sandra Pina is worried.

“If I shut down again, I won’t be able to put food on the table or pay my rent … But that was the story of my life – I always struggle to find a way.”

Comments are closed.