Isaac Shoshan, Israeli Spy Who Posed as an Arab, Is Lifeless at 96

TEL AVIV – Isaac Shoshan, a Syria-born Israeli undercover agent who posed as an Arab early on in his career, participated in bombings and assassinations before making major contributions to the country’s espionage methods, died on December 28 in Tel Aviv . He was 96 years old.

His daughter Eti confirmed the death in Ichilov Hospital. He’s had a stroke, she said.

In a tribute on Twitter, former Prime Minister Ehud Barak, who once served in an Israeli intelligence unit that was designed by Mr. Shoshan, said that Mr. Shoshan “risked his life again and again” on behalf of Israel.

“Generations of warriors have learned their craft at his feet,” he added, “so have I.”

Mr. Shoshan was born as Zaki Shasho in Aleppo, Syria, in 1924 into an Arabic-speaking Jewish family. He studied at a French-speaking school, learned Hebrew at Orthodox Jewish schools and, as a teenager, was a member of the Zionist Hebrew Scouts. At the age of 18, motivated by his Zionism, he traveled to Palestine, which was then ruled by Great Britain, and was recruited within two years by the Jewish underground fighting force Palmach.

During his training, he was transferred to a secret unit called the Arab Platoon. It was made up of Jews who could pass as Arabs and was tasked with gathering information, carrying out sabotage and targeted murders.

The unit was set up in anticipation of a “civil war in Palestine between Jews and Arabs,” said Yoav Gelber, professor and historian of the period.

The unit’s members, most of them immigrants from Arab countries, were trained in information gathering and covert communications – such as Morse Code – as well as command tactics and the use of explosives. They have also studied Islam and Arab customs extensively so that they can live as Arabs without arousing suspicion.

Mr. Shoshan participated in intelligence operations after the United Nations decided in 1947 to divide Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, resulting in clashes that would turn into war.

In February 1948, however, he was asked to use another aspect of his training: the murder of a Palestinian leader, Sheikh Nimr al-Khatib, who was allegedly traveling to Palestine with weapons from Lebanon.

Gunmen were supposed to shoot the sheikh’s car, and Mr. Shoshan, as a seeming Arab bystander, was instructed to “run back and help but actually make sure the sheikh was dead and if not, quit the job, off with my gun,” said he in an interview in 2002.

The sheikh was shot dead in his car – the assassins “sprayed it with submachine gun fire,” Shoshan said – but survived after British soldiers prevented Mr Shoshan from reaching it. The badly wounded sheikh left Palestine and no longer played an active role in the war.

Shortly afterwards, Mr. Shoshan and another member of the Arab platoon were sent to a garage in Haifa, Israel, where intelligence agencies reported that a car bomb was being assembled.

“The owners never suspected us,” said Shoshan. “Of course they didn’t want to let our car in, but they agreed to let us use the toilet for a moment.”

That was long enough to activate a timed fuse on an explosive device and escape. Minutes later, a massive explosion rocked the entire area, destroying the garage and several adjacent buildings, killing at least five people and injuring many more.

After the withdrawal of British forces from Palestine and Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948, Arab train agents were deployed to neighboring Arab countries to gather information and thwart perceived threats.

“Although we were sent to gather information, we also saw ourselves as soldiers and looked for opportunities to act,” Shoshan said.

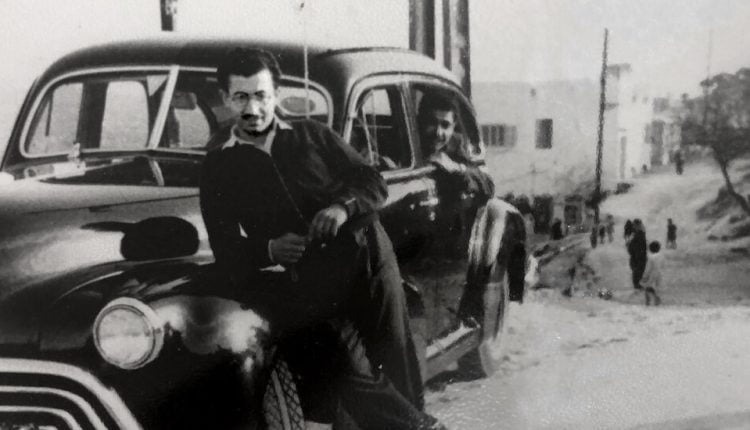

Sent to Beirut, he and his colleagues bought a kiosk and an Oldsmobile, which they used as a taxi to cover their activities.

At one point the unit was ordered to plant a bomb on a wealthy Lebanese man’s luxury yacht. (They were told that Adolf Hitler used it during World War II.) The secret service suggested converting the ship into a gunship for use against the Jews. Ensuring the explosion did not sink the yacht, but damaged it so badly that it could not be used for military operations.

The team’s most important operation – a mission to assassinate Lebanese Prime Minister Riad al-Suhl – was scheduled to take place in December 1948. Mr. Shoshan and the others devised a plan to kill the prime minister as they followed his movements. But the operation was called off at the last moment by senior Israeli leaders, much to Shoshan’s great disappointment, according to his report.

During his two years in Beirut, Mr. Shoshan met relatives of those killed in the Haifa garage bombing. They spoke to him freely, thinking he was a Palestinian.

“Before that I never thought of the people who were killed there,” Shoshan recalled in the book “Men of Secrets, Men of Mystery” (1990), which he wrote with Rafi Sutton, a former secret service colleague. “And there in Beirut an old Arab sat across from me and wept for his two sons who were killed in the explosion in which I had participated.”

This encounter was one of the events that changed Mr. Shoshan’s thinking, his son Yaakov later said. “Papa always knew that if we only use force,” he said, “it would only lead to more wars, and he always supported the” two states for two peoples “solution.”

The arrest and execution of some Arab platoon members eventually led Israel to abandon the use of Jewish spies who assimilated with Arabs. Mr. Shoshan turned to recruiting and managing Arab agents, a role that prompted him to turn them into turncoats.

“It turned out that he was gifted with a talent for this job too,” said co-author Sutton in an interview. “Agents are problematic and you need to know when to lie to you, when to tell you the truth, and how not to let them blackmail you and take control of the relationship between you without affecting their willingness to work with you . ”

Mr. Shoshan later pushed for the assimilation program to be resumed, which led to the formation of Sayeret Matkal, a special operations spy unit. The unit was formed to gather information from the heart of enemy countries, including through the use of fighters trained to use Arab cover. Its members included a young Benjamin Netanyahu, now Prime Minister, and his predecessor, Mr Barak, who commanded it.

Mr. Shoshan was given the responsibility to train the members who posed as Arabs.

He was involved in creating the cover story for Eli Cohen, the Israeli spy who penetrated the upper echelons of the Syrian regime in the 1960s but was ultimately exposed and executed. (Mr. Cohen’s story was recently dramatized on the Netflix series “The Spy,” starring Sacha Baron Cohen.)

Ms. Shoshan retired in 1982, but has been mobilized from time to time by the Israeli intelligence service Mossad to train agents and sometimes take part in operations herself.

When he went undercover, he would take on the role of an Arab old man pretending to need help – for example, to enter a building to make an urgent call, or to occasionally contact a recruiting target. An older man, its leaders believed, aroused less suspicion.

Comments are closed.