The Finish of a Beloved Delhi Establishment

Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and provides a behind-the-scenes look at how our journalism comes together.

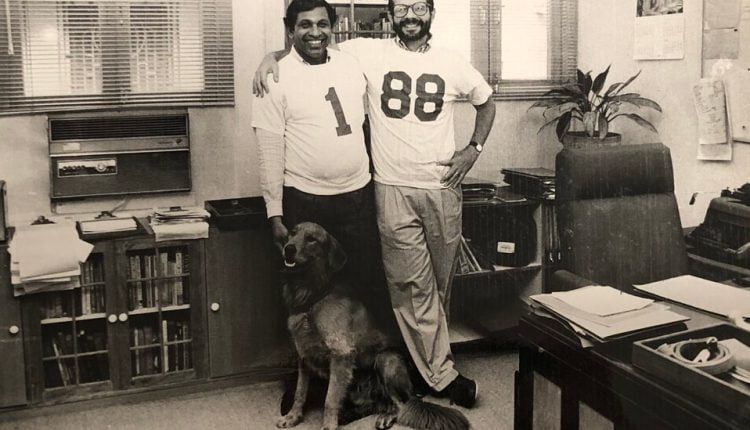

NEW DELHI – For over half a century, Parambaloth Joseph Anthony, a clever and kind man, served as the New York Times’ secret weapon in India.

As the New Delhi office manager from the mid-1960s to a few years ago, Mr. Anthony, whom everyone called PJ, played as many roles as anyone else at The Times. He was an accountant, a translator, a guide, an archivist, a Newshound who could follow 10 stories at a time, and a beloved and indispensable friend of many correspondents and their families.

A former correspondent even called him Kojak after the 1970s. The reason was that many years ago, after a group of people got sick at a dinner party, PJ took it upon himself to do some research. Sure enough, he solved the puzzle.

After scouting the neighborhood and entertaining staff, he learned that a jealous servant had sprinkled gasoline on the chicken served that evening in order to sabotage the cook. PJ shared his findings and gently suggested that the servant be replaced.

But now PJ is gone.

Last week, PJ died of complications related to Covid-19 at the age of 82.

PJ was my entry point in India, just as it was for so many other correspondents 50 years ago. He was standing on the curb of the airport to track me and my family down with a shy smile on their faces after a grueling 20-hour journey. As an office manager in New Delhi, I’ve seen him almost every day for the past three years and I can still hear his voice in my ear. I find it hard to believe that I will never see him again.

His job was to run the Times’ small office in Connaught Place in the heart of the Indian capital and to work closely with the office managers. (He tended to refer to the office managers as “doctor”, though far from it.) The office managers are responsible for journalism, and the office managers are responsible for almost everything else – handling expenses, renewing visas , the translation of documents and, in the case of India, the decryption of one of the most confusing countries on earth. PJ loved it every day.

Even in his 70s and 80s, he was often the first in the office and you could always tell when he was approaching. The street dogs in front of the office would go crazy and howl with joy.

Then a stooped figure with thick glasses and sometimes a hanging trench coat emerged from the fog of Delhi, and a cloud of shabby dogs enveloped him.

He always came with a bag of bones and pieces of meat. That was the first thing PJ did every morning. He fed the strays.

He “defied time,” said John Burns, who served as Delhi office manager in the 1990s. “In the data-retrieval age, he fervently held onto the gospel of the printed word and built a towering fortress in the Delhi office of stacked newspapers dating back to the Nehru age,” said Burns.

It was Jim Yardley, another office manager, who discovered about eight years ago after PJ broke his hip that PJ had worked long past retirement age and that his retirement benefits were in excess of his salary. Still, PJ didn’t want to stop.

“I explained that there are many ways to define retirement, of course,” recalls Yardley.

Thus began a somewhat unorthodox agreement that initially confused downstream office managers and other employees and lasted until March when India imposed a strict lockdown that closed the Times office. Every day, PJ volunteered at the office, where he continued to sit and help behind his towering fortress of newspapers.

As a devout Catholic, he brought the most delicious box of chewy chocolate brownies with him every Christmas. Each night before leaving the office, he would get up, walk to the door, squeeze his palms together, and give a slight bow.

The Delhi employees described him as firm, formal, stoic, skeptical, demanding and above all extremely loyal.

Once, after getting upset about something, he grumbled to Hari Kumar, a seasoned reporter, “I gave my life to the New York Times.”

Suhasini Raj, another reporter in the Delhi office, once asked him if he ever felt sad if an office manager moved every three or four years, as they usually do.

“You can’t get sentimental,” PJ advised her. “So many office managers have come and gone that if I started crying, if everyone came and went, I would cry all my life.”

Recognition…Suhasini Raj

Comments are closed.