A Covid Christmas Involves Bethlehem

BETHLEHEM, West Bank – The Church of the Nativity has closed and most souvenir shops have closed. Hotels that usually sold out months in advance were abandoned.

One of the few signs of life on the main street in the old town of Bethlehem last Friday was the chirping of a few birds and stray cats cleaning up an overflowing garbage can.

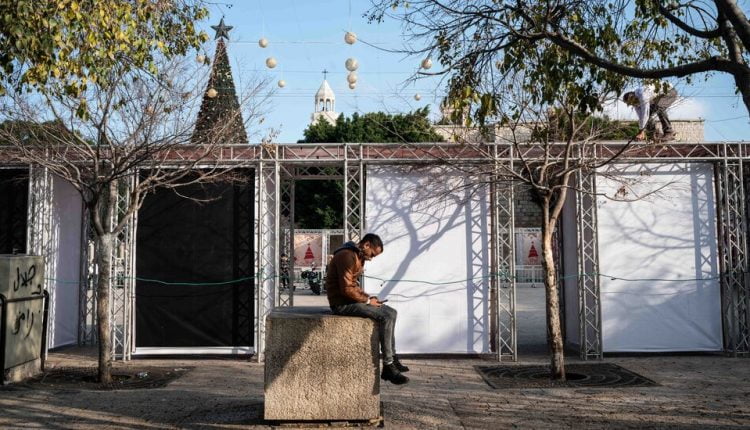

Earlier this month, few people attended the tree-lighting ceremony in Manger Square, an event that usually heralds the metamorphosis of the quiet West Bank city of Bethlehem into one of the main seasonal attractions of international Christianity.

The coronavirus pandemic put a damper on Christmas at the point where everything should have started.

“Great sadness,” said Father Ibrahim Shomali, Chancellor of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, about this year’s celebrations. “We are very frustrated, but what can we do? We have to accept reality and do the right thing. “

Midnight Mass at the Church of the Nativity is usually one of the social events of the year in the occupied West Bank. The old limestone church takes on the atmosphere of a glittering film premiere, as diplomats and Palestinian officials in bespoke suits and elegant clothes emerge from columns of shiny BMWs and Mercedes cars.

This year, the ceremony will be limited to church officials, a handful of European diplomats and the Mayor of Bethlehem. The Palestinian Authority imposed tough anti-virus restrictions in Bethlehem on December 10, established checkpoints around its perimeter, ordered restaurants, cafes, schools and gyms to be closed, and banned almost all large gatherings.

Bethlehem has around 1,000 confirmed, active cases of Covid-19, according to official figures, although the actual number is believed to be much higher. All intensive care beds in hospitals are occupied, the Ministry of Health said.

During a recent visit, the sprawling 222-room lobby of the Bethlehem Hotel was silent. The leather sofas and chairs were empty, the lights and heating were off, and a fine layer of dust collected on the coffee tables.

“There’s usually no place to sit this time of year,” said Elias al-Arja, the hotel owner, who wore a winter coat and a large black mask. “It usually gets so crowded that there is little freedom of movement.”

Since March, when authorities discovered the first cases of the virus in the Bethlehem area, the hotel has had problems paying its debts, according to Mr al-Arja. He had to lay off all but two of his 80 employees. To pay off the debt, he sold his second home in Ramallah and a piece of land in Jericho.

“It was devastating,” he said.

Before the pandemic, the West Bank tourism industry, which is heavily dependent on the Christmas business in Bethlehem, was expecting its best year in two decades. The West Bank had more than three million visitors last year, tourism officials said.

And despite competition from Israeli travel companies and the challenges of doing business under occupation, Palestinian travel and tourism companies discontinued, offered new travel routes, and forecast further growth in 2020.

“We went from our highest to the lowest,” said Tony Khashram, director of the Holy Land Incoming Tour Operators Association. “Everything fell apart in no time.”

Tens of thousands of people in the tourism industry – including tour guides, tour operators, gift shop owners, and restaurant and hotel workers – have lost their jobs, according to estimates by the Ministry of Tourism. Tour operators struggle to pay off debts and collect hundreds of thousands of dollars in payments from overseas partners.

Retailers are also devastated. The few traders who opened their stores said the absence of tourists this year had heightened their sense of desperation over the economic fallout from the pandemic.

“The whole world came for Christmas last year,” said Sami Khamis, whose tea shop near Manger Square sells a specialty tea with whole pieces of fresh sage, ginger, mint, rosemary and cinnamon. “But I barely make enough money now to put food on the table. This is a catastrophic situation. “

The seven or eight souvenir shops nearby, which usually sell kaffiyehs, baby Jesus dolls on straw beds, and olive wood crosses embedded with a bottle of earth from the Mount of Olives, were all closed.

In his office facing the Church of the Nativity, Mayor Anton Salman said he was sad that Bethlehem would not celebrate Christmas as usual, but stressed that public health was of the utmost importance. He caught the virus last month.

“We have had difficult circumstances at Christmas in the past,” he said, referring to previous violent conflicts with Israel. “But the pandemic is something completely different – there are so many unknowns.”

He said the city would not give up its traditions, only downsize it.

The Manger Square Christmas market, he said, was on a single day on Sunday instead of the usual two. The audience for the annual Boy Scout Parade, where dozens of boys and girls march through Bethlehem with Palestinian hymns and Christmas carols on Christmas Eve, will be limited to local residents.

“We don’t feel like it’s Christmas,” said Lorette Zoughbi, 66, who saw the tree lights on TV even though it was just down the street from her apartment. “There is no special atmosphere. These days feel like all other days that come and go. “

Bethlehem’s Christians, who are largely Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox, were once the majority. But the Christian population has shrunk due to emigration, while the Muslim population has grown. Now, like all Palestinian cities in the West Bank, Bethlehem is predominantly Muslim.

Ms. Zoughbi, a member of a prominent Christian family in Bethlehem, felt so deprived of the Christmas cheer that she and her husband didn’t even bother pulling their large tree out of camp. Instead, they put a small piece of metal in a corner of their apartment.

For many Palestinian Christians, the worst part of this Christmas season is canceling extended family gatherings.

Ms. Zoughbi’s clan usually gathers for dinner of qidreh, a rice and lamb dish, in a large restaurant with 150 of her relatives, often followed by an evening of drumming and singing Arabic Christmas carols.

“These are some of the only times we can all get together,” she said.

Nihaya Musleh, a resident of Beit Sahour, just east of Bethlehem, said she planned to host Harumiya, a local tradition where men – or, in her case, the family matriarch – following their married daughters and sisters on a special occasion Invite home meal 40 days before Christmas.

Ms. Musleh said she and her son invited 28 family members to their home for lunch and promised to enforce social distancing.

But after cooking for two days, Ms. Musleh said, her daughter-in-law tested positive for the virus, so she canceled.

“I would be lying if I told you I was not unhappy about missing Harumiya,” she said. “But I’m glad we heard about the positive test the day before – it was a gift from God.”

Comments are closed.