Arts Bailout in U.Okay. Buys Time, however No Peace of Thoughts

LIVERPOOL, England – One afternoon Liam Naughton stood in the main room of the Invisible Wind Factory, a huge music and arts space he runs in a former industrial area of Liverpool that has largely been closed since March.

“We could build a runway here,” he said excitedly. “The idea is that people walk around while hot bands are playing.” Marshals could enforce social distancing, he added.

Mr. Naughton’s head was full of wild ideas from a sudden change in happiness. In early October, he assumed he would have to close the company completely and lay off its 60 employees, he said. Then, on October 12, the UK government gave him $ 300,000 from a $ 2 billion bailout fund to arts organizations in England to help prevent the shutdown.

“It was such a relief,” he said. “We only needed a small syringe to be back in the game.”

There was only one problem, he added: what if there is no vaccine by the end of the money? It’s impossible for venues like him to make a profit when they have to cut back on numbers and enforce social distancing, he said.

“Nobody’s out of the woods,” said Mr. Naughton, sounding unhappy for the first time.

In July, British cultural institutions praised the government for its art bailout, one of the most generous in Europe. The announcement was heard jealously in the United States, where art institutions received little help from the state. (Jesse Green, co-chief theater critic of the New York Times, called it “a powerful message about the centrality of the arts in a modern democracy”.)

That month, some again lauded the government as the money went to over 2,000 arts organizations, from England’s national ballet to London’s Fabric nightclub.

But for many, the joy may not last long. The terms of the grant state that they must be issued by March 31 of next year. After that, on April 1st, many will again have the prospect of layoffs or closings if institutions cannot operate profitably with socially distant limits.

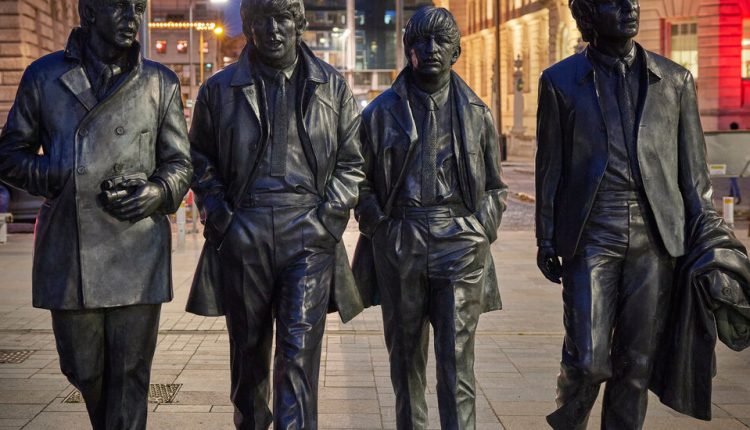

Liverpool – home of the Beatles and the Tate Liverpool, whose tourism is based on culture – was a big winner of the state bailout. More than 40 organizations in the city received grants totaling about £ 7 million, about $ 9 million. Winners included household names like the Cavern Club, where the Beatles played early shows, and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, as well as lesser-known institutions like FACT, a digital art museum, and the Unity Theater, a local playhouse.

In interviews last week, 11 recipients said they were grateful for the funding, with audible relief. The money would be used to pay rent and wages and stage detached work, they said. “It’s life support that keeps the ventilator going,” said Craig Pennington, founder of Future Yard, a new music venue in nearby Birkenhead, which received approximately $ 78,000.

But they also said they didn’t know what would come in the spring if the pandemic didn’t subside. “We will be able to make losses or make significant savings,” said Michael Eakin, executive director of the Liverpool Philharmonic, which received nearly $ 1 million. That could include layoffs, he added.

Some of the city’s art institutions and music venues have already cut jobs. On October 5, the National Museums Liverpool – an umbrella organization that includes the city’s International Slavery Museum and the Walker Art Gallery – announced that it was cutting a fifth of its workforce. Laura Pye, its director, said in a telephone interview that the number of visitors to museums is only 17 percent of the prepandemic levels. She didn’t expect them to recover until 2024, she said.

And the city’s arts organization knows exactly how quickly the rules can change.

On October 12, Prime Minister Boris Johnson ordered all pubs in the city to be closed to combat rising coronavirus cases. Cultural institutions were allowed to remain open, but the restrictions seemed to affect visitor numbers. On a recent afternoon visit to the Walker Art Gallery, only eight people looked around at a photo retrospective by Linda McCartney. Three employees stood bored at the entrance counter.

The new restrictions also banned cultural institutions from serving alcohol unless accompanied by a substantial meal, cutting off an important source of income. On the first Friday after the new restrictions went into effect, the Hot Water Comedy Club was the only cultural venue open in town with a detached audience of 70 in the basement. Nobody drank anything stronger than soda.

“The stress is the infinite change,” said Binty Blair, one of the club’s owners. “You could tell us to close next week.”

The Hot Water Comedy Club received about $ 580,000 for the rescue operation, but other nighttime venues in the city have already gone under. A handful of music venues closed in the summer, including the Zanzibar Club, which has been campaigning for the city’s bands for 30 years.

Jon Keats, a director of the Cavern Club, said he has already laid off 30 employees. He was now focused on spending the bailout money, he said, and would use half of the grant to stage a series of concerts with solo musicians performing on the venue’s stages, streamed live on the internet.

“The money shouldn’t open up to us again,” he said, “as we can’t with social distancing.” But that will help get people back on stage. “

Several other cultural institutions, including the Everyman and Playhouse theaters, said they would try to use the money to help the freelance artists in Liverpool who have been hard hit by the pandemic.

One afternoon Ellie Hurt, 27, a freelance theater director, was working one shift at the Bellefield Nursing Home. When Britain went into lockdown in March, she was working on a show at the National Theater in London, she said. Suddenly unemployed, she found that she had not qualified for the UK freelance support programs because too much of her income came from working in bars and restaurants.

She needed work and applied for 40 jobs, including at banks and grocery stores. Only the nursing home provider returned to her, she said.

Now, said Ms. Hurt, she was responsible for organizing activities like bingo for the residents of the Bellefield Nursing Home. “It’s probably the best thing I’ll bring to cultural work for a while,” she added.

She was delighted that so many venues in Liverpool were getting money, she said, but added, “I think this is a little too little late. Everyone had to retrain. “

Although many respondents shared Ms. Hurt’s concerns, they also knew one thing: they would do anything to survive next spring, with or without government help.

Mr. Blair of the Hot Water Comedy Club said he built the club from scratch with his brother and even did the joinery for the stage. It was now a social media sensation in the UK with clips from Paul Smith, his compère, who had gone viral on Instagram. “I did this for 10 years without making any money,” said Blair. “I do it because I love to see people laugh.”

He never expected to get anything from the government, he said, because Liverpool have always been hit hard. The government surprised him this time, he said, but if he didn’t get any more money, it wouldn’t matter.

“If I had to do a homeless comedy club on the street,” he said, “I would.”

Comments are closed.