Germany’s Far Proper Reunified, Too, Making It A lot Stronger

BERLIN – They called him the “Führer of Berlin”.

Ingo Hasselbach had been a secret neo-Nazi in communist East Berlin, but the fall of the Berlin Wall brought him out of the shadows. He allied himself with western extremists in the united city, organized right-wing workshops, led street fights with leftists and celebrated Hitler’s birthday. He dreamed of a right-wing extremist party in the parliament of a reunified Germany.

Today the right-wing extremist party Alternative for Germany, known by the German initials AfD, is the main opposition in parliament. Their leaders march side by side with right-wing extremists in street protests. And its power base is the former communist east.

“Reunification was a huge boost for the far right,” said Hasselbach, who left the neo-Nazi scene years ago and is now helping others to do the same. “The neo-Nazis were the first to be reunited. We laid the foundation for a party like the AfD. There are things that we used to say that have become mainstream today. “

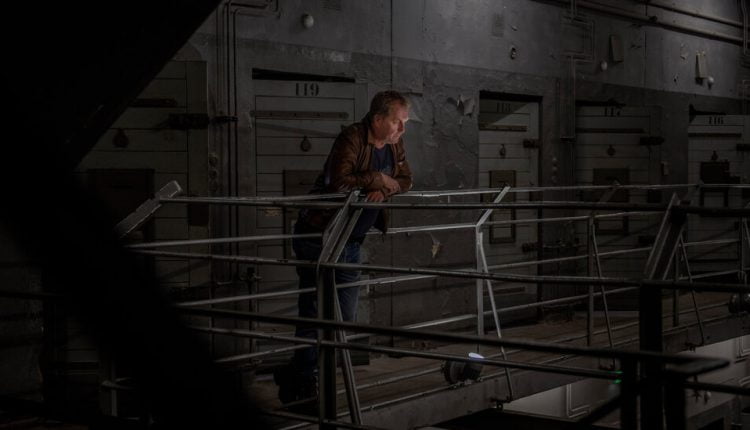

Recognition…Dietmar Gust

On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of reunification on Saturday, Germany can rightly celebrate that it is an economic powerhouse and a flourishing liberal democracy. However, reunification has another, seldom mentioned legacy: the unification, empowerment and disclosure of a right-wing extremist movement that has developed into a disruptive political force and a terrorist threat, not least within key state institutions such as the military and police.

“Today’s right-wing extremism in Germany cannot be understood without reunification,” said Matthias Quent, an expert on right-wing extremism and director of an institute that studies democracy and civil society in eastern Thuringia. “It freed the neo-Nazis in the east from their subterranean existence and gave right-wingers in the west access to a pool of new recruits and entire areas in which to move without too much control.”

For years, German officials trusted that a right-wing extremist party could never be re-elected to parliament and rejected the idea of right-wing extremist terrorist networks. However, some fear that the right-wing extremist structures established in the years after reunification laid the foundation for a resurgence that has become visible in the last 15 months.

Right-wing extremist terrorists killed a regional politician on his veranda near downtown Kassel, attacked a synagogue in the eastern city of Halle and shot nine people with a migration background in the western city of Hanau.

That summer, the government took the drastic step of disbanding an entire military company in the special forces after explosives, a machine gun and SS paraphernalia were found on the property of a sergeant major in the East Saxon countryside. A disproportionately large number – around half – of those suspected of right-wing extremism within this unit, the KSK, came from the former East, the commandant said.

Nationalism and xenophobia are more deeply rooted in the former East, where the grueling history of World War II has never been as deeply confronted on a social level as in the former West. The AfD achieved twice as many votes in the eastern states, where the number of right-wing extremist hate crimes is higher than in the western states.

Officially, there were no Nazis in old East Germany. The regime defined itself in the tradition of the communists who opposed fascism and led to a state doctrine of memory that effectively freed it from the atrocities during the war. Right-wing extremist mobs who beat up foreign workers from other socialist countries such as Cuba or Angola were classified as “rowdies” who were misled by Western propaganda.

But a strong neo-Nazi movement grew underground. In 1987, Bernd Wagner, a young police officer in East Berlin, estimated that there were 15,000 “local” violent neo-Nazis, 1,000 of whom were repeat offenders. His report was quickly locked away.

Two years later, when tens of thousands took to the streets in anti-communist protests that ultimately overthrew the regime, pro-democracy activists weren’t the only protesters.

“The skinheads marched too,” recalled Mr. Wagner.

Before reunification, the far-right scene in West Germany was small and aging, but now Western neo-Nazis flocked east to offer “reconstruction aid” and unexpectedly found refuge. Behind the wall, the East was frozen in time, a largely homogeneous white country in which nationalism was allowed to live on.

“The leaders of the western scene thought they were in paradise,” recalls Hasselbach.

Since then, the east has been the home of choice for several prominent Western extremists. Götz Kubitschek, a leading right-wing extremist intellectual from Swabia who wants to preserve Germany’s “ethno-cultural identity”, bought a rural mansion in the east that serves as the headquarters of his right-wing extremist publishing house and research institute.

So does Björn Höcke and Andreas Kalbitz, two Westerners who became leaders of the most radical factions of the AfD in the former East.

“The East has become a kind of retreat for the extreme right,” said Quent, “a place where Germany is still Germany and where men are still men.”

But being in love with the East is also strategic, he said. “Right-wing extremists have a meaning: ‘We cannot win in the West, but we can win in the East, and then we will face the West from a position of strength.'”

The reunification also provided a physical space for far-right members to move around and exercise. Secret neo-Nazi training camps were held in abandoned Soviet military bases. In one of them, on the Baltic Sea island of Rügen, Mr. Hasselbach took part in workshops on forging identity documents, making bombs, guerrilla warfare and “silent killing”.

The first years after reunification were so turbulent that the security services were unable to control this converging extremist movement.

“In the eastern states there was no mature structure for a domestic intelligence service,” said Thomas Haldenwang, president of the domestic intelligence service, in an interview. “The agencies in the new states had to be built from scratch.”

In the early 1990s a wave of racist violence swept through Germany, much of it in the east. Foreigners were hunted down, beaten up and sometimes killed. Asylum houses were set on fire. Immigrant buses were attacked. Sometimes eastern viewers watched, clapped or joined in.

“You could see that something was shifting and not just marginally,” said historian Volkhard Knigge. “Otherwise the AfD would not be so strong today.”

In the early 1990s, Mr. Knigge moved east to manage the memorial in the former Buchenwald concentration camp. He was shocked by the abundance of Nazi memorabilia such as Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” that are for sale at flea markets and by the multitude of angry young neo-Nazis who gathered in the historic theater square and shouted xenophobic slogans.

“We thought democracy had won,” Knigge said. “The West thought this was the end of the story. For nationalists, however, this was a revision of history. “

Reunification brought together two types of nationalism, said Anetta Kahane, a Jewish anti-racism activist – western-style nationalist conservatism and a more radical eastern social revolutionary diversity. Neither of them had alone been powerful enough to stimulate a political movement.

“It was the marriage of the two that made the AfD possible,” said Ms. Kahane, who heads the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, named after a black Angolan who was beaten to death by neo-Nazis with a baseball bat in less than two months after of reunification.

For most Germans, the new century was marked by progress. Chancellor Angela Merkel, an Easterner, embodied the liberal values of the West. When the country hosted the soccer World Cup in 2006, a sovereign multicultural Germany could be seen, which many at the time called a “summer fairy tale”.

“I wanted to believe that we are like this as a country – and I believed it,” said Tanjev Schultz, author and professor of journalism. “But it wasn’t true.”

That summer, the National Socialist Underground, a right-wing extremist terrorist group that had emerged from the extremist networks formed in East Germany, was involved in a rampage with immigrants that the police would not discover until 2011.

Between 2000 and 2007, the group killed nine immigrants and one police officer, despite paid intelligence informants helping to hide their leaders and building their network.

Mr Hasselbach said he was not surprised to see recent revelations about far-right infiltration of security services. When he was still a neo-Nazi, friendly police officers would warn them about robberies or give them files from left-wing enemies.

It was the deadly violence in the early 1990s that made Mr. Hasselbach leave the neo-Nazi scene in 1992. Two girls and their grandmother were killed in an arson attack on the house of a Turkish family. He spent years underground trying to escape threats from his former far-right compatriots. He then co-founded Exit Germany, an organization that helps extremists to leave their networks, with Mr. Wagner, the former East German police officer.

The fate of the AfD has subsided in recent years and has flowed. According to polls, voter support has fallen to around 10 percent during the pandemic. But the fringes are radicalizing, say intelligence officials.

It worries Mr. Hasselbach and Mr. Wagner.

“The willingness to use violence today is greater than ever before,” said Hasselbach.

“Westerners have no sense of how fragile things are,” said Wagner. “The elites do not see the post-democratic decline. The Eastern countries have seen a system collapse before. “

Comments are closed.