How a Trinidadian Communist Invented London’s ‘Notting Hill Carnival’

The Notting Hill Carnival was canceled last year. But without the efforts of Claudia Jones, it probably wouldn’t exist at all.

For the London-based Caribbean diaspora, there may never have been a quieter weekend than August 2020, when the Notting Hill Carnival would normally have taken place.

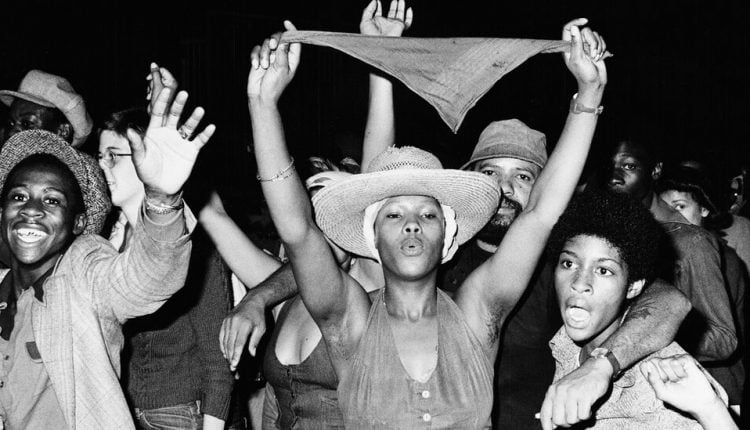

There is no shortage of sensory festival experiences in England, from music in Glastonbury to Diwali celebrations in Leicester. But there’s nothing better than attending the Notting Hill Carnival. Step out of the subway station, hop off the bus or hop off your bike, and step into the irresistible buzz of the festivities by stepping off the sidewalk into the street.

The hum you hear is the combined sound of hundreds of steel pans knocking out calypso. floats from the decadently decorated band; the sweet whispers of the girl with the afro kissing the boy with the fading; the soca bass of your favorite sound system; the rustle of the proudest feathers of a peacock performer; pinging a bikini strap; the clank of the jerk drums; the sloshing of sweet punch; the clapping back from elders who still consider the carnival their personal reunion party, and the enthusiastic screams of teenagers attending for the first time.

This buzz is heard by over a million attendees at the Notting Hill Carnival each year, but also in other parts of the UK, at the St Pauls, Nottingham and Cardiff Carnivals, and in cities around the world: Port of Spain during Trinidad and Tobago Carnival ; Rio during Carnival; Toronto during Caribana; and New York during J’Ouvert. Of course, many of these celebrations were canceled in 2020 due to pandemic restrictions.

God we missed carnival last year.

After a summer of Black Brits embroiled in a protest movement – one that may have emerged from protests against Black Lives Matter in the United States but was used to portray our particular struggles with racial violence, including the findings that Black people in the UK are twice as likely to die in police custody as whites – so many of us desperately wanted to be distracted to lean into the parts of our culture that are not openly mired in pain. Carnival has always been a dependable publication, an opportunity to celebrate and reconnect with the community.

The Notting Hill Carnival is sometimes referred to as “Europe’s biggest street party” and focuses on the music, food and culture of the Caribbean diaspora. But it has its roots as a place of anti-racist resistance and insurrection, until the original Caribbean Carnival was founded in 1959 by a Trinidadian activist, writer, and editor named Claudia Jones.

Jones brought her rerun of Carnival to London at a different time when people needed it badly. The first “Caribbean Carnival” took place in the dead of winter in January 1959, after a series of Black British protests against police violence in areas of England, including Notting Hill. These protests took place against the background of the migration of the “windrush” generation to England: the mass wave of non-white immigration to Great Britain in the post-war period. Over several decades, around half a million immigrants came from Caribbean countries. (The name “Windrush” refers to a ship, the HMT Empire Windrush, which brought workers in 1948.) The cultural contribution of this generation has a number of creative projects from the 2004 novel (and the subsequent television series) “Small Island” to ” Small Ax ”, the anthology of films by director Steve McQueen.

Jones was an atypical member of the Windrush generation. She was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1915 and lived in Harlem for 30 years before moving to London in 1955. Her journey back to her life there was fraught with difficulties: she was affected by tuberculosis as a teenager and in the US she was jailed by the McCarran Internal Security Act for her political work with the Communist Party before she was eventually exiled to the UK. One of the most widespread portraits of Jones shows her reading an edition of “Pages from the Life of a Worker” by the American communist leader William Z. Foster.

After what Jones’s biographer Carole Boyce Davies described as “a lukewarm reception” from the British Communist Party, unresponsive to Jones’s anti-racist efforts, Jones decided to devote her formidable organizational skills to uplifting the British black community.

Along with activist Amy Ashwood Garvey, Jones co-founded one of Britain’s first major black newspapers, The West Indian Gazette (known as WIG), in 1958. By January 1959, she had launched the Caribbean Carnival, an indoor event in London’s St. Pancras Town Hall. Sponsored by WIG and televised by the BBC, the Carnival featured a number of elements including dance, music, and a Caribbean Carnival Queen beauty pageant.

“We need something to get the taste of Notting Hill out of our mouth,” Jones is reported to have said at the beginning of the carnival. She later titled the brochure for the event “The art of a people is the genesis of their freedom”. In the brochure, she refers directly to how Notting Hill and Nottingham have “brought West Indians together in the UK like never before”. The carnival lasted annually until her death in 1964, after which it was “interrupted” in 1965 in her honor, before returning to the streets in 1966.

Colin Prescod, a black history archivist and sociologist whose mother, actress and singer Pearl Prescod, was a close friend of Jones, moved from Trinidad to Notting Hill as a child and still lives there today. Mr Prescod believes that there was widespread anti-racist awareness in Notting Hill which made it fertile ground for the development of Carnival.

“I think the North Kensington area has entered a proto-black lives-matter movement,” he said of the area in the late 1950s. Those feelings were further cemented after the murder of Kelso Cochrane, an aspiring law student and carpenter from Antigua, who was stabbed to death by a gang of white people in Notting Hill in May 1959.

“The Notting Hill Carnival was one of the most beautiful means of protest,” said Fiona Compton, a Trinidad Historian, photographer and Carnival ambassador from Great Britain. Jones “looked at many different ways of making change in society, and she realized that Carnival was the way because it showed that we create joy too.”

Jones was an inherently charismatic figure. “She smoked, she drank and she was an extrovert,” said Frances Anne Solomon, a director who is currently making a movie about Jones. “She loved to party.” Ms. Solomon pointed out that, despite living with tuberculosis that would claim her life in 1965, Jones “had a personality that attracted people so that she could make people do anything. Everyone loved Claudia. “

With Carnival, Jones sparked a wave of solidarity among the Black Brits. Her forward-looking attitude towards organizing communities through celebration is still reflected in recent attempts to position black joy as an act of resistance and resilience.

From those beginnings, the carnival grew into an annual street party thanks to the artists and organizers who followed Jones’ lead. In 1966, Rhaune Laslett, a community leader in Notting Hill, enlivened the festival as Notting Hill Fayre, who brought Russell Henderson’s steel-pan band to the streets, in an impromptu performance that is believed to have sparked the carnival process we know today. Leslie Palmer, a Trinidadian activist, introduced Jamaican sound systems to the Carnival in 1973, drawing the crowd and opening the festival beyond the traditions of the Eastern Caribbean Islands.

Mr. Prescod noted that at the time there was “real confrontation, big argument” in favor of including sound systems, which were about shows revolving around the emerging reggae genre played over sophisticated amplification systems. But the sound systems got stuck, he said, because “this suddenly brought masses of more people to the carnival”.

Prescod also pointed out, “Carnival has two roots – it has two feet. One foot here in the UK and the other in the Caribbean. “

In fact, the Notting Hill Carnival was modeled on carnival celebrations in the Caribbean, which were themselves “the intervention of the emancipated Africans,” said Attillah Springer, writer and activist. Enslaved people in areas of the Caribbean, especially Trinidad, took elements of European masquerade balls and infiltrated them using their own rituals and traditions to find the freedom to masquerade – or “do mas” – and become different characters .

After emancipation, many of these traditions were fused into carnival celebrations, including J’Ouvert, a ritual of abandonment before dawn that often dips night owls in mud and oil. “For many people (myself included) J’Ouvert is the most important part of the celebration,” said Ms. Springer. “It’s dirty and dangerous and anonymous. It’s also very spiritual and apologetically political. “Ms. Springer called Jones the” ultimate Jouvayist … to make her aware of the transformative nature of those hours before sunrise. “

In 2020, the Notting Hill festival was silent for the first time in decades. It has been a particularly difficult blow in the face of yet another summer of racial justice protests and a pandemic that has disproportionately struck the black British Caribbean community in Britain. With the Notting Hill Carnival now happening in August, there is still hope that the Carnival could take place in 2021. In both cases, however, his mind remains. For Black Brits, in Ms. Compton’s words, it’s “our Mecca” or “our Christmas” as a friend described it to me on Twitter.

At my very first Carnival in Notting Hill, as a little kid in my father’s arms, I remember desperately wanting to climb over the barriers and join the beautiful women darting down the street to the beat of the drums. I remember a woman who fluttered her feathers on me. I valued her whom I previously thought were only princesses.

The last year has been calm and difficult. But the carnival will rise again. And if so, I have no doubt that with the knowledge in our hearts that Carnival can be a political space and a festival of resilience and renewal, we will return to the streets as energetic and radicalized as Claudia Jones would have liked it.

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff is a journalist, podcast host, and editor-in-chief of Gal-Dem magazine. She is the editor of two anthologies, “Black Joy” and “Mother Country: Real Stories from the Windrush Children,” and lives in London.

Produced by Veronica Chambers, Marcelle Hopkins, Dahlia Kozlowsky, Ruru Kuo, Antonio de Luca, Adam Sternbergh, Dodai Stewart and Amanda Webster.

Photo and Video Credit: Group 1, Christopher Pillitz / Getty Images; Richard Braine / PYMCA, Universal Images Group, via Getty Images; ITN via Getty Images. Group 2, Monte Fresco / Mirrorpix, via Getty Images; Hulton Archives via Getty Images; Daily Mirror, Mirrorpix via Getty Images. Group 3, Daily Mirror / Mirrorpix, via Getty Images (still images); British Movietone / AP (video). Group 4, PYMCA / Universal Images Group, via Getty Images; ITN via Getty Images; Steve Eason / Hulton Archive, via Getty Images. Group 5, PYMCA / Universal Images Group, via Getty Images (still images); ITN, via Getty Images (video)

Comments are closed.