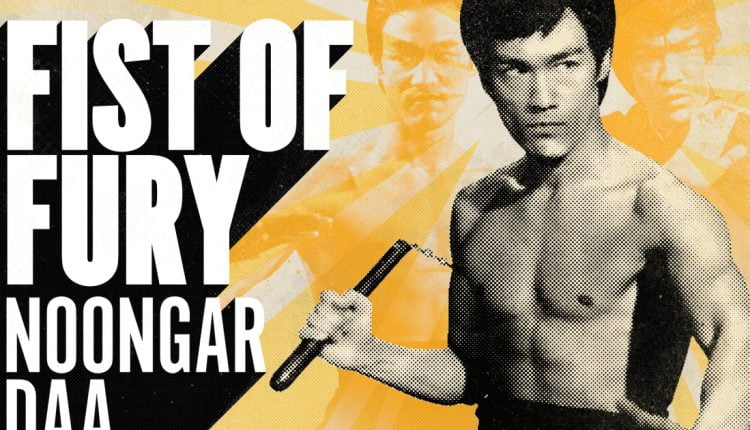

Inspiring cultures: Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury dubbed into Noongar | Arts and Tradition Information

It’s the movie that inspired a generation: the flying kicks, the angry blows, the whirlwind sound effects.

Fist of Fury is the classic 1972 Bruce Lee film that took the world by storm.

Tragically, Lee died a year after it was made, aged just 32.

But his films have had an enduring global impact, not least on a family of indigenous Noongar in Australia.

And now, in a world first, Fist of Fury has been dubbed into the Noongar language.

“I love everything that Bruce Lee stands for,” says director Kylie Bracknell of Al Jazeera. “As we say in our community, actions speak louder than words.”

An avowed Bruce Lee fan, Bracknell remembers watching his films with her brothers and putting up movie posters on bedroom walls at home.

Bracknell – whose indigenous cultural name is Kaarljilba Kaardn – says she not only admired the martial arts master’s kung fu skills, but also his philosophy and approach to life.

Noongar speakers worked with Hong Kong Cantonese speakers on translation and dubbing [Courtesy Perth Festival]It was these traits that also correlated with their own Noongar culture and inspired them to produce Fist of Fury which was dubbed into their traditional language.

The project is not just about novelty.

Indigenous languages on the continent now known as Australia have been threatened since the British colonization began in 1788.

In a recent article, Jane Simpson, Chair of Indigenous Linguistics at the Australian National University, noted that between 300 and 700 languages were previously spoken on the continent.

The last census in 2016 found that only 160 of these languages were spoken at home.

“And of those, only 13 traditional indigenous languages are spoken by children,” said Simpson. “It means that in 60 years there will be only 13 of the Australian languages left, unless something is done now to encourage these children to keep speaking their language.”

Journey of discovery

Bracknell’s own language trip began at the age of 13 after her grandfather passed away.

Kylie Bracknell became interested in the indigenous Noongar language at the age of 13 and learned from her grandmother’s sisters [Courtesy Perth Festival]She remembers noticing various language books in his house and asked her grandmother why her family didn’t speak her original language, Noongar.

Kylie Bracknell became interested in the indigenous Noongar language at the age of 13 and learned from her grandmother’s sisters [Courtesy Perth Festival]She remembers noticing various language books in his house and asked her grandmother why her family didn’t speak her original language, Noongar.

Her grandmother stated that when she was 14 she had been sent away to work for a white family and had “no chance” of keeping her culture and language safe from older family members when the Australian government’s policies of assimilation tried to target various indigenous people Eradicate cultures and languages across the continent.

But Bracknell was determined, and her desire to learn her original language led her to visit some relatives who still retained their Noongar language.

“So I sat with my grandmother’s sisters and learned our language,” she says.

“At the time, I had no idea that in 2021 I was going to premiere a dub of a Bruce Lee movie. I just wanted to connect the missing pieces to who I am and understand why that part of our cultural identity has been suppressed. “

She says she learned this the hard way – being betrayed and “growled” at by the older people in the group.

But Bracknell soon realized that these were simply methods of raising children their own way, and just like Bruce Lee’s philosophy, of testing their skills in order to make them stronger.

“I just wanted to make them proud, and to make old people proud, you have to listen and wear things on your chin,” she says. “They give you their time and energy because they care and because they also want you to make them proud.”

February 21st marks the United Nations’ International Mother Language Day, when the different languages of the world are to be celebrated and preserved.

The UN has stated that 43 percent of the world’s 6,000 languages are currently threatened, including many indigenous languages. Although indigenous peoples make up less than 6 percent of the world’s population, they speak more than 4,000 of the world’s languages.

Such languages - like Noongar – are threatened by colonization and past and present politics, which – intentional or not – contribute to the erosion of indigenous languages.

Bracknell tells Al Jazeera that she didn’t speak Noongar publicly until she was 24 when she started working for theater companies in Western Australia. She would eventually produce a Noongar version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, entitled Hecate, which premiered at the Perth Festival last year.

“I always wanted to do legitimate research and use my heart to speak it with that old tone, with the being that my teachers spoke it before I shared it,” she says.

The team is working on the dubbing, trying to make sure the mouth movements of the original and Noongar versions match [Courtesy Perth Festival]The Fist of Fury project was inspired by a 2013 Navajo dubbed release of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, according to Bracknell.

The team is working on the dubbing, trying to make sure the mouth movements of the original and Noongar versions match [Courtesy Perth Festival]The Fist of Fury project was inspired by a 2013 Navajo dubbed release of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, according to Bracknell.

She didn’t want to repeat Star Wars, however, and felt that the Bruce Lee film “would reach all generations” and was “a little more art house”.

Most importantly, Bracknell felt that Fist of Fury was a film that “really speaks to the physical expression we honor in our language. It’s not just about what’s coming out of your mouth, it’s also about your body expression. “

“Too many people think language is a spoken form. You forget that our language is in your physical expression, ”she says. “That influenced the choice of Bruce Lee and Kung Fu.”

Translation challenge

Dubbing the film was no easy task.

“It was difficult to translate because you are responsible for an interpretation,” recalls Bracknell. “And you are responsible for recognizing the importance of the original text and conversations.”

“The difficulty with dubbing is that you have to adjust the movement of the actors’ mouths on the screen. It’s not just about the difficulty of translation, but also about the art of giving the screen actor the gravity and strength that he has in his mother tongue. “

The production team worked with a Cantonese translator from Hong Kong to ensure the correct translation process, which turned out to be a meticulous process.

“We work in what is arguably the most demanding language in the world – Cantonese – and so they will expect us to get this right,” she says. “It’s their story, it’s their movie.”

The process proved worthwhile for their research on the Noongar language, for example when they found a word for “older brother” that they did not know before.

Bracknell believes that dubbing classic movies into indigenous languages can help people feel proud of their culture [Courtesy Perth Festival]Such language acquisition and survival projects are slowly being implemented in Australia as the cultural and social importance of language is better recognized.

Bracknell believes that dubbing classic movies into indigenous languages can help people feel proud of their culture [Courtesy Perth Festival]Such language acquisition and survival projects are slowly being implemented in Australia as the cultural and social importance of language is better recognized.

A program with various regional languages has recently been set up in Western Australian prisons to be taught where appropriate.

“There is a strong link between language and culture, so this new program is designed to help Aboriginal prisoners reconnect with their own people, practices and beliefs,” Corrective Services Minister Francis Logan said in a media statement.

“Research shows that teaching Aboriginal languages produces positive outcomes in personal and community development, including good health and wellbeing, self-respect, empowerment, cultural identity, complacency, and belonging.”

That such a program, as opposed to schools, has to be conducted in prisons is evidence of the ongoing negative effects of colonization on indigenous communities, with young Aboriginal people more likely to go to prison than to university.

With this in mind, Bracknell says projects like Fist of Fury “are really important because they are exactly what will stimulate, inspire and motivate our younger generation to be proud of what they have and what the generations are proud of before them were able to protect and pass on.

“You see your own people accept it,” she says. “They see real people – and it is their people from their community – who accept the language and enjoy the joy that comes from it.”

Comments are closed.